A Test of Character

Of all the chaos during the tumultuous months of 2016, one particular moment stands out among them. I was early to a lesson, and as I waited in my car, I listened to the first speech to be delivered by the newly elected President of the United States, Donald Trump. Looking back on it, I remember thinking how surreal it all seemed, that US voters could listen to the jarring cadence, the strange intonation, the batshit statements and think it amounted to someone who should have ready access to the world’s largest nuclear arsenal. If I’m honest with myself, I can’t have been wholly surprised by the result, coming as it did so soon after the UK had done the unthinkable and voted to leave the European Union. Although different, both results felt intrinsically linked, with many overlaps as we would later learn, but in that moment I felt a sense of political vertigo that has never really dissipated in the years since.

What sticks in my mind wasn’t so much the speech, but what happened when I finally sat down with my class. In front of me were the usual ragtag group of software developers I often found myself working with, intelligent and thoughtful guys, often prone to rather matter of fact communication, which was why I was there. Matter of fact in German is one thing, but when translated into English, it can often come across as arrogant. We went through the initial pleasantries at the beginning of the session, when one of the group asked how I was. I wasn’t prepared for what I ended up saying, but what poured out of me was the internal confusion I was feeling in that moment. I said I wasn’t great, the Trump vote the day before and the Brexit vote a few months ago really concerned me for the future. Clearly it was a watershed moment, but of what I had no real idea. When I finished, I looked around the room, and was surprised to see only blank expressions. As I pondered what they might be thinking, one of the developers spoke up “It’s not that important. It’s in America, we live in Germany”.

I was shocked, but I also remember a sudden and all encompassing anger that rose in the very pit of my stomach. As a language & communications trainer, I had met my fair share of obtuse types, those people that seem to delight in saying exactly the wrong thing at exactly the wrong time. Looking across the table, it was obvious this wasn’t that, but the realisation almost made me more angry. “How could anyone be so naive!?” I thought, “to believe that what happened in the most powerful country in the world wouldn’t send tremors everywhere else”. Thankfully I kept myself in check, caging my immediate anger for release at a more suitable and secluded moment in time.

One reason I was able to show some level of restraint was that I essentially agreed with the point being made. America may be highly influential, but this was Germany, a country of refreshingly sensible people. If any place could withstand whatever Trump and Brexit represented, I was confident it was Germany, a nation designed with a vital purpose: to never allow extremism to take hold again, to never forget what happens when it does, and to be vigilant for any signs that it might. I may be showing my own naivety here, perhaps the zealousness of the convert, but from the Grundgesetz (German Constitution) down, I felt we stood a good chance of weathering the storm.

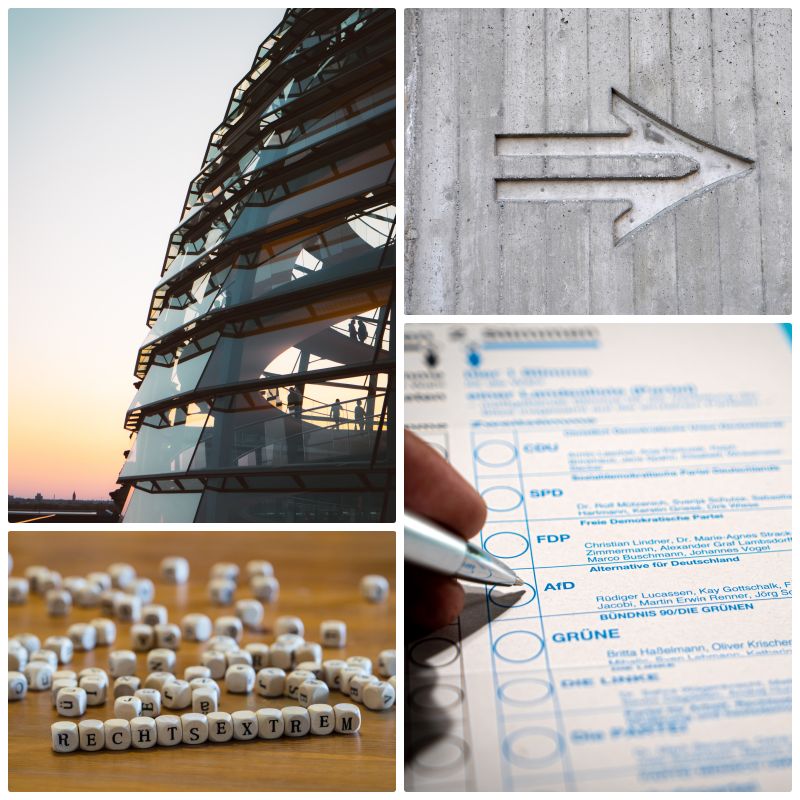

From where I sit writing this in 2023, I feel less confident of Germany’s ability to do so. For the last 12 months, I’ve watched Germany begin a process I’ve seen twice before. One might argue, and I have some sympathy for this position, that Germany’s swing rightwards has been going on far longer, but it is only in the last three years that it has accelerated, and certainly only in the last year that the real impact has begun to be felt in all areas of public debate. Certainly since the turn of the year, national politicians have seemingly ignored the warning signs wholesale, and are intent on putting on a German language remake of their own 2016, by stoking division and embracing culture war politics.

All the markers are there to be found: politicians pandering to right-wing voters, the breakdown of any compromise between government and opposition, the failure of the media to hold anyone truly to account, the willingness of public figures to grasp the nettle of the culture war and wave it in the face of anyone that will listen. At the same time as the national debate has soured, the real issues facing the country have only increased. Growing poverty is matched only by the increasing gap between the wealthy and the poor, the failure to recognise stability comes at the cost of progress, the lack of investment, a complete inability of politics to recognise or address the real problems faced by people now, and those that will undoubtedly come in the future. In turn, these failures at the top, coupled with the deeply felt wounds of the pandemic, have only increased a sense that our democratic institutions are failing.

Studies and polls bear out this reading of the current German moment. Polling has seen the far-right AfD party reach joint 2nd nationally, a shock to the system and also to those who have so frequently seen right-wing extremism as an issue only in the east of the country. Moreover, a recent study from the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung suggests that right-wing attitudes are becoming more widespread than before, with 20% agreeing with the statement that “our country increasingly resembles a dictatorship rather than a democracy”, while 6% of responders wanted the return of an authoritarian single party run state, and 8% overall holding clear right-wing views.

Rather than countering the threat of populist politics, it seems there are far too many in Germany hoping to harness it for their own ends. Whether that’s politicians happy to stand on a platform with right-wingers, or those cultivating the right in order to build or increase their public profile, the imagined “Brandmauer” or firewall that was meant to distance the traditional political parties from the AfD looks ever weaker. Finger pointing, the most useless of activities, appears to be the only response. As we have seen across the world, every step rightwards tarnishes the public debate, and emboldens supporters on the streets of Germany, making life worse for everyone and especially for those who are the focus of extremist anger.

Despite my hopes in 2016, that Germany might be better prepared than many for the right-wing shift of politics seen in other countries, we are now in the midst of the same problem seen across the democratic world. Yet, I remain optimistic. I know from prior experience that once the right-wing shift begins, it is nearly impossible to stop it, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it can’t be defeated. While it remains easier to divide voters than to unite them, what can hold the line are the democratic institutions put in place some 73 years ago. After all, people don’t build flood defences thinking they will never be used. Germany was refounded in 1949, and in so doing tried to establish a system that could prevent the country's capture by extremism. Now, the test of our system is coming, and I hope we can withstand it.

Proofreader: @ScandiTina

Image Credit

Photo by Sean Ferigan on Unsplash

Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

Photo by Steinar Engeland on Unsplash

Photo by Christian Lue on Unsplash