Mint Sauce and the Germans

A few nights ago, I was discussing with a friend the differences between British and German barbecues. I explained that growing up in the 80s and early 90s there were several high profile incidents of salmonella poisoning, and as a result, everyone seemed deeply concerned with food poisoning, especially from not cooking meat properly. As a child it felt like every year, as barbecue season began, news outlets and magazine-shows would warn the public about the dangers of undercooking meat, especially chicken. I’m fairly sure there were sporadic national ad campaigns too. For some reason, the British couldn’t cook chicken correctly, or so it seemed, meaning every family barbecue was food poisoning Russian roulette. Either you received a dose of the Norovirus, or you were forced to eat a drumstick that had been carefully incinerated to a smoking husk. The topic of British food is always one Germans enjoy, and my friend laughed at the confirmation of their bias about how terrible it can be. They leaned forward, and through the laughs they jokingly asked ‘Did you put mint sauce on it too?’. I smiled politely then quickly changed the subject.

My friend’s “joke” is one I’ve heard many times before, not just from them, but from a lot of Germans I’ve met over the years. When the topic of British food comes up, a comment about mint sauce is never far away. No matter how many Michelin stars British restaurants are given, or how many TV chefs we export around the world, there’s an unshakable belief among many Germans that British food is terrible, an opinion that is underscored by the British use of mint sauce. When I point out that there is not much difference between German and British food other than approach or that mint sauce only ever goes with lamb, I’m given a long and often severe lecture on the universal truth of inedible British food. Other times I’m simply ridiculed. This is especially the case if I’m speaking with Germans born before the 1980s, and in fairness to them, the 1970s and 80s were not high points for British cooking. Reading British cookbooks from that era is to marvel at the audacity and bravery of the British, willing to experiment with ingredients that have no right to exist in the same dish, or celebrating the mediocrity of beige-coloured buffet food. However, there’s no clear reason why mint sauce should take the brunt of the ridicule, nor why it has become the poster condiment for all that is wrong with British cuisine.

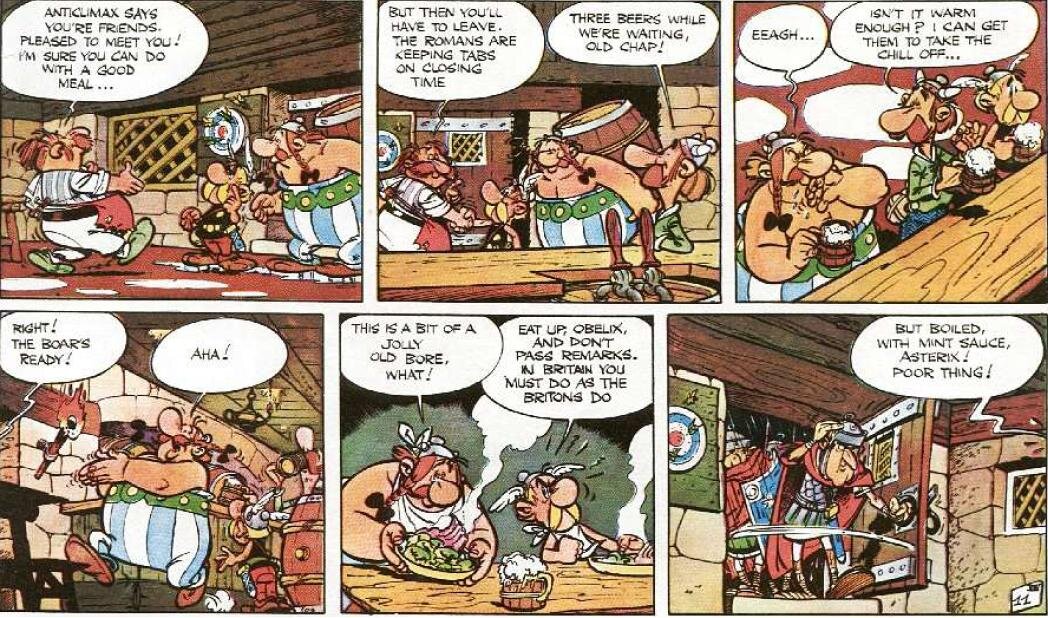

The mint sauce trope in Germany does seem to originate from the same era that gave us Pot Noodle, Findus Crispy Pancakes, and salads that inexplicably included jelly, namely the 1970s and 80s. It also appears that the crucial intervention of one of Britain’s oldest rivals at roughly the same time had a large impact on how the continent understands the British diet. France’s most famous comic book character, Asterix the Gaul, took some delight in lampooning the culinary deficiencies of their cousins across the channel. In the fantastic ‘Asterix in Britain’ (published 1965) there’s a famous panel that shows the titular character, and his companion Obelix, “enjoying” British style roast boar, with the latter complaining that it’s been boiled and covered with a minty condiment. Still an ever popular character among Germans today, Asterix has done irreversible damage to the reputation of British cooking in much of Europe.

As tempting as it might be to lay the blame for British culinary misconceptions on the French, there is another way that the stereotype of bad British food has been perpetuated over the years since Asterix took a swipe at boar and mint sauce. For decades, Germans have sent their children to the UK to improve their English language skills, and for decades German children have returned traumatised by the experience of daily fish fingers, frozen ready meals, and baked beans served by host families. Clearly the British are their own worst enemies, and when presented with an opportunity to dispel the rumours, they instead double down. Whether because of miserly tendency, food culture differences or financial pressure, the negative reports from exchange students had a ripple effect back in Germany, which only confirms all the biases Germans assumed to be gospel truth already. Now we have a situation where several generations of Germans have not only heard about the blandness of British food, but also have first-hand experience of it.

That being said, this knowledge hasn’t put Germans off holidaying in Britain, and it might be hoped that the tourist experience would enlighten the British food sceptics. In some ways it does, but sadly not in any way we might consider positive. When faced with the reality of British food, and the discovery it isn’t a god awful mess, Germans quickly change their opinions. However, what’s remembered is the more extreme ends of the dietary spectrum, such as a hearty English breakfast or fish and chips. People tend to come back with a positive story, but the terrible British food trope is now replaced with an unhealthy British food trope, which given the two dishes mentioned is as hard to argue.

Of course, holiday experiences, student exchanges and Asterix comics don’t fully explain why Germans have a fixation on mint sauce. For years I’ve wondered about this, and over time I may have found an answer to the mint sauce puzzle. While leading a workshop for a team of German engineers working in the UK, one participant asked me why the British insisted on having mint sauce with everything. I answered the question with one of my own, as I’ve done many times before, asking them why they thought this. I expected another reference to Asterix or some holiday horror story, but it turned out that on a business trip, the participant’s British counterpart had taken the whole German team for dinner at a traditional British pub. When everyone had ordered, and just before the food arrived, one of the bar staff placed a basket of condiments on the table. In the basket were sachets of all types, and nestled under the mustard and ketchup were several green packets of mint sauce. My participant had concluded, with irrefutable German logic, that all these sauces were intended to be eaten with the food they had ordered. When the food arrived, the participant merrily opened a mint sauce packet. Despite the polite objections of their host, they poured not one, but two sachets (it was a large lasagne apparently) on top and began to eat. The participant told me the ruined lasagne tasted only of minty pasta and cheese, but they continued to eat for fear of offending their British colleague. It later transpired that the host had also remained silent for fear of making the German guest look foolish. Since hearing this story, I’ve made sure to tell Germans travelling to Britain that mint sauce is not a general use condiment.

Although there’s a growing appreciation in Germany for British food, thanks to ready access to British cooking shows via streaming platforms, or influencer-content on social media, there are still holdouts, convinced that whatever the British are eating, it’s not worth thinking about. I’ll continue to point out that both countries share a similar food history, with obvious divergences, but I’m not foolish enough to believe anyone is convinced by that argument. Defending British cuisine from the erroneous assumptions of Germans will continue to be a Sisyphean task - after all, every country has their own edible embarrassments to uncover. Perhaps Britain simply has more than most countries, I mean, just wait until Germany discovers the pork and egg loaf.

Proofreader: @ScandiTina

Image Credit