Mint Sauce and the Germans

A few nights ago, I was discussing with a friend the differences between British and German barbecues. I told them that I had grown up constantly worried about food poisoning from not cooking meat properly. As a child it felt like every year, as barbecue season began, news outlets and magazine-shows would constantly warn the public about the dangers of undercooking chicken. I’m fairly sure there were sporadic national ad campaigns too. For some reason, the British couldn’t cook chicken, or so it seemed, meaning every family barbecue was food poisoning Russian roulette. My German friend laughed and then inquired ‘Did you put mint sauce on it too?’. I smiled and then changed the subject.

My friend’s “joke” is one I’ve heard many times before. When the topic of British food comes up, a comment about mint sauce is never far away. There is an unshakable belief among many Germans that British food is terrible, underscored by the British use of mint sauce. When I point out that there is not so much difference between German and British food or that mint sauce only ever goes with lamb, I’m often given a long and severe lecture on how wrong I am, in other cases I’m simply ridiculed. This is especially the case for Germans born before the 1980s. In fairness, the 1970s and 80s were not high points for British cooking. Reading cookbooks from this era is to marvel at the audacity and bravery of the British, willing to experiment with ingredients that have no right to exist in the same dish.

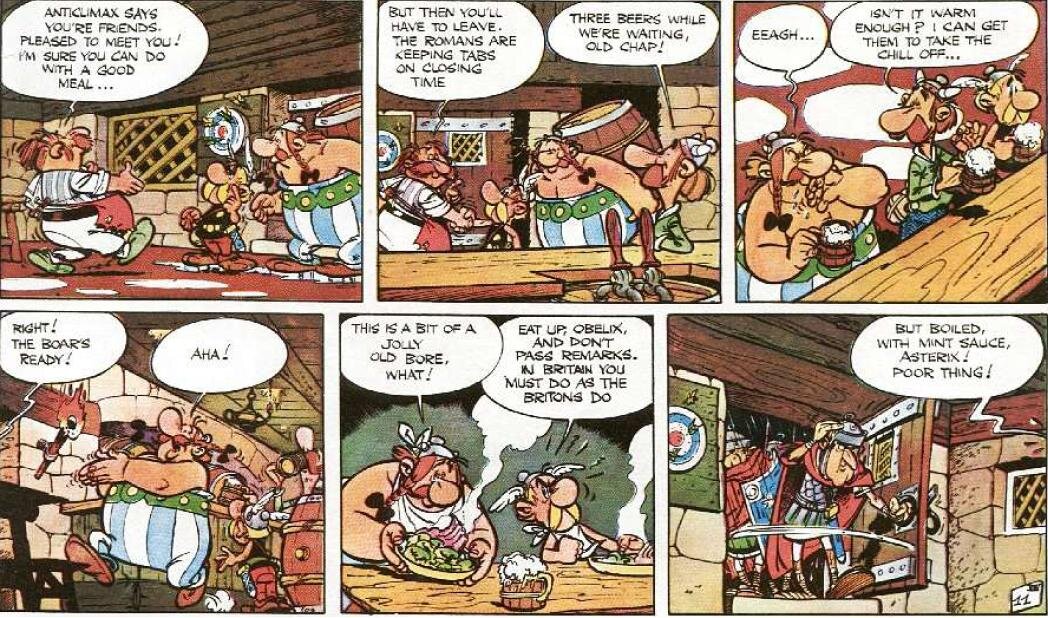

The mint sauce trope in Germany seems to originate from this era too. Given the amount of people who reference it in conversation, the trope was popularised by France’s most famous comic book character, Asterix the Gaul. Still a popular character among Germans today, Asterix has done terrible damage to the reputation of British cuisine. Asterix in Britain (published 1965) is famous for a panel that shows the titular character and his companion Obelix “enjoying” British cooked roast boar, with the latter complaining that it’s been boiled and covered with the minty condiment.

As tempting as it might be to lay the blame for British culinary misconceptions on the French, it is often the British who are their own worst enemy. For decades, it has been popular for middle class Germans to send their children to England to improve their English language skills. Organised by schools, these trips can be as long as a month and require German students to live with host families. Many German children come back traumatised by their experience of crispy pancakes, frozen ready meals and baked beans served by their hosts. Whether because of frugality, food culture differences or financial pressure, the negative reports from exchange students has a ripple effect back in Germany.

Now we have a situation where several generations of Germans have not only heard about the blandness of British food but also have first-hand experience of it. This hasn’t put off Germans from holidaying in Britain and it could be hoped that the tourist experience would enlighten the sceptics. In some ways it does. However, what seems to be remembered is the extremes, such as a hearty English breakfast or fish and chips. People tend to come back with a positive story, but the terrible British food trope is replaced with an unhealthy British food trope, which given the two dishes mentioned is as hard to argue.

Of course, student exchanges and Asterix still don’t fully explain why many Germans have a fixation on mint sauce. For years I wondered about this, having to bite my tongue at work or releasing some choice expletives outside the office when confronted by references to mint sauce covered everything.

I may have found the answer to the mint sauce puzzle. While leading a workshop for a team of German engineers working in the UK, one of the participants asked me why the British insisted on having mint sauce with everything. I asked, as I had done with others many times before, why they thought this, expecting to receive another reference to Asterix or some holiday horror story. It turned out that on a business trip, the participant’s British counterpart had decided to take the whole German team for dinner at a traditional British pub. When everyone had ordered, and just before the food arrived, one of the bar staff had placed a basket of condiments on the table. In the basket were sachets of all types and nestled under the mustard and ketchup were several green packets of mint sauce. He had concluded, logically, that all these sauces were intended to be eaten with the food they ordered, which is the type of thinking I’ve come to expect here in Germany. When the food arrived, the participant had merrily begun opening the mint sauce packet to pour on their lasagne. Despite the polite objections of the host, the participant poured not one, but two packets (it was a large lasagne apparently) on top and began to eat. The participant told me the ruined lasagne tasted only of minty pasta and cheese, but they continued to eat for fear of offending their British host. It later transpired that the host had also remained silent for fear of making the German guest look foolish. Face saving, clearly, is just as important to both cultures. Now I make sure to tell Germans travelling to Britain that mint sauce is not a general use condiment.

Although there has been a growing appreciation in Germany for British food, there are still many holdouts, convinced that whatever the British are eating it’s not worth thinking about. Both countries may share a similar food history, with obvious divergences, but I don’t think many people are convinced by that argument. Defending British cuisine from the erroneous assumptions of Germans may well be a Sisyphean task. I mean, just wait until Germany discovers the pork and egg loaf.

Image Credit