A Trap For Fools

Way back in 2010, I remember watching an interview with the then would-be Prime Minister David Cameron. Although it was a over a decade ago, one particular answer he gave has often come back to me in the years since his elevation to the most important office of state in the United Kingdom, and his ignominious resignation following the Brexit Referendum six years later. The question was a relatively simple one: ’Why do you want to be Prime Minister?’. Cameron’s reply was equally straightforward: he smiled and said simply "I think I’ll be good at it". It was the kind of sentiment that only a man like David Cameron could have offered. It’s delivered with a confidence incubated in the finest schools and universities in the country, places that take the idea of being ‘born to rule’ very seriously. Why wouldn’t they? After all, Cameron’s former school of Eton has given us twenty former Prime Ministers, his former university of Oxford counts thirty former PMs, and between the two institutions, they have produced a total of fourteen.

One reason I return to this interview is the fact Cameron’s answer was so wide of the mark. While many believe his successors to be worse Prime Ministers, I consider his tenure in office to be have been far more destructive. While Theresa May, Boris Johnson, and Liz Truss presided over the rapid decline of Britain, David Cameron began the process, in part due to the hubris expressed in that interview answer in 2010. It was the same confidence that saw Cameron fatefully promise a referendum on Brexit, a topic only 15% of voters in 2015 thought important; the same ego that believed pandering to the far-right was a no-risk strategy. When he won a surprise majority in the 2015 election, that same confidence led him to have a referendum with no safeguards, no requirement for a majority decision, and no plan for what happened if he lost.

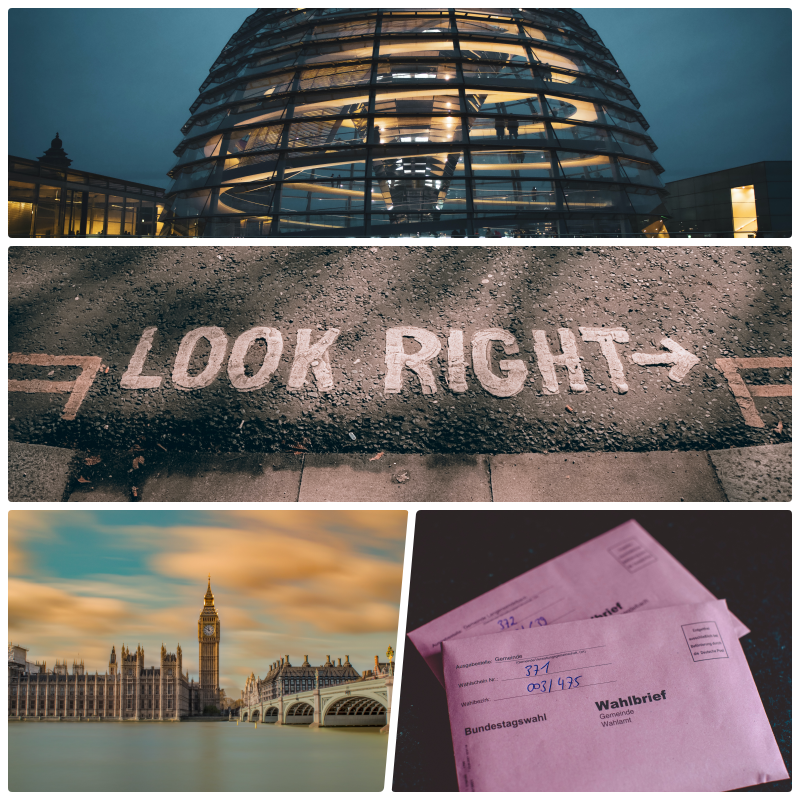

Another reason I can’t get the gurning vision of David Cameron from my mind is that when I watch the current discourse happening in German politics, I feel a disturbing sense of déjà vu. This week has been dominated by statements made by CDU leader Friedrich Merz, concerning the various violent incidents reported over New Year’s Eve in Berlin. According to reports, 145 people were arrested for violent attacks on emergency services in Germany’s capital, with much of the focus being on the backgrounds of those arrested. The term ‘Migranthintergrund’ (migration background) has been bandied about readily, and has become a central pillar of another tedious debate on the nature of integration in Germany, or rather the inability of certain groups to integrate. Merz himself identified the perpetrators as ‘aus der arabischen Welt’ (from the Arab world) and said that the group, which included 45 German nationals, were ”young people from the Arab world who are not willing to follow the rules here in Germany. They enjoy challenging this state.” Merz would then go on to claim the cultural backgrounds of the arrested were to blame, that they were not taught discipline by their parents, and described children of migrants as "kleine Paschas" (Little Pashas).

The backlash to these statements was swift, with many pointing out that Merz had lumped wholly different ethnicities together under the term ‘arabischen Welt’, and moreover, had ignored the fact that many involved were actually born in Germany. Rightly, the commentators pointed out, Merz was following a clear strategy of appealing to the prejudices and fears of Germans at large, and moreover, using the rhetoric and talking points of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland.

You may wonder what all this has to do with David Cameron? Well, as I watched the interview with the leader of Germany’s largest opposition party, I saw the unmistakable signs of the same confidence, and the same hubris, in the countenance of Friedrich Merz. While Merz may not have been educated in the same institutions as David Cameron, they both seem to exhibit the same "born to rule" attitude. Not only that, the same ill-fated strategy seems to be in play, powered by an equally blind conviction. Merz is making the same mistake Cameron did in 2015: he believes he can tame the far-right, co-opt their talking points, and win their votes without any consequences. In short, he appears to be striding right into the same trap that brought the UK to its knees.

How did we get here? To unpick that question, we have to go back 12 months. It’s perhaps forgotten that the German government, nicknamed “die Ampelkoalition” (traffic light coalition), is only just over a year old, having formed in December 2021. The coalition of the SPD, Greens and FDP faced an in-tray that ranged from benefits reform, infrastructural renewal, increasing housing stock, investment in education, and expanding renewable energy, all of which would have been hard in a normal year, let alone in one that included the tail end of a pandemic and a war in Europe.

With the stakes so high, the attention of media outlets was laser focused on government decisions, with waves of justified and unjustified criticism coming from almost all sides of the political spectrum, and frequently on an hourly basis. As many problems as this presented to the German government, it also presented a massive question to the new opposition party in Berlin: the CDU. While they might have taken some measure of enjoyment from watching the government take a kicking, so much criticism from the media, global partners, academics, journalists, experts, and many others has left little room for the official opposition. When the newly minted CDU leader Friedrich Merz finally took up his position, he wasn’t so much chasing the government, he was chasing the pack of critics as well. The challenge wasn’t to oppose, but to simply be heard opposing.

The reaction of the CDU was to fight for relevance. This began with aggressive debating in the Bundestag. At no point would the government be credited for anything. Policies that the CDU disagreed with were attacked, but so were ones that the CDU broadly agreed with. When Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced massive new investment in the military to meet NATO commitments, Merz agreed, but then went on to point out that they didn’t go far enough. When weapons were to be delivered, it wasn’t enough. When the government made commitments, they were too meagre. If the government made a decisive decision, it was too slow. Much of this is Opposition 101, and given the volume of 2022, it was clear that more would be needed.

Simply criticising every policy will only take an opposition so far, eventually they will need to present another vision to the country, one that counters what’s already available. Ultimately, the problem the CDU faces is one that many political parties face today: how to form a coalition of voters from a fractured polity? Germany isn’t as polarised as the UK or the US is, but for the CDU to regain it’s place at the summit of German politics, it needs to pull votes from all sides. This is a near impossible task. For instance, can the CDU be more Green than the Green Party? Competence may well pull votes from the SPD, but that relies on the SPD screwing up, which isn’t always a guarantee. Taking votes from the FDP is possible, they have a lot of common ground, but they are the smallest party in government, so slim pickings at best. Where then will the votes come from?

It seems Merz, like Cameron before him, has decided to look further right for the votes he needs, or perhaps wants, a decision that is setting in motion a trap that far-right parties have been setting for the centre-right for as long as those terms have been in existence. Merz is trying to eat the lunch of the far-right AfD - how else can we explain the rhetoric of Merz through the end of 2022 and into early 2023? What Merz seems to have missed from the example of Cameron, is that this path only ever leads one way. Once the respectable right starts speaking in the voice of the extreme, it shifts the Overton Window of acceptable discourse. By lending the CDU’s credibility to far-right, they may win voters over, but they also leave themselves open to being infected by the far-right at the same time. How long before the policies sound the same? How long before it influences member selection? How long before the discussions over common ground lead to very real discussions of right-wing coalitions?

Personally I have no idea, but I know it took David Cameron six years to lose his position of PM to the far-right of British politics, another year for the far-right to capture the strategic vision of the Tory Party, and another two years until PM Boris Johnson purged his party of centrists (21 were expelled in 2019). Now, the Tory party of 2023 looks and sound more like the UKIP of 2015, or its successor, The Brexit Party. They say a week is a long time in politics, but that nine year movement from centrist Cameron to far-right Johnson was rapid. Can Merz beat that record? Maybe, but one thing I’m certain of: Friedrich Merz is confident he can.

Proofreader: @ScandiTina

Image Credit

Foto von Skitterphoto

Foto von Pixabay

Foto von Leon Seibert auf Unsplash

Foto von Mika Baumeister auf Unsplash

Foto von Markus Spiske auf Unsplash

Foto von hoch3media auf Unsplash