Variations On A Theme

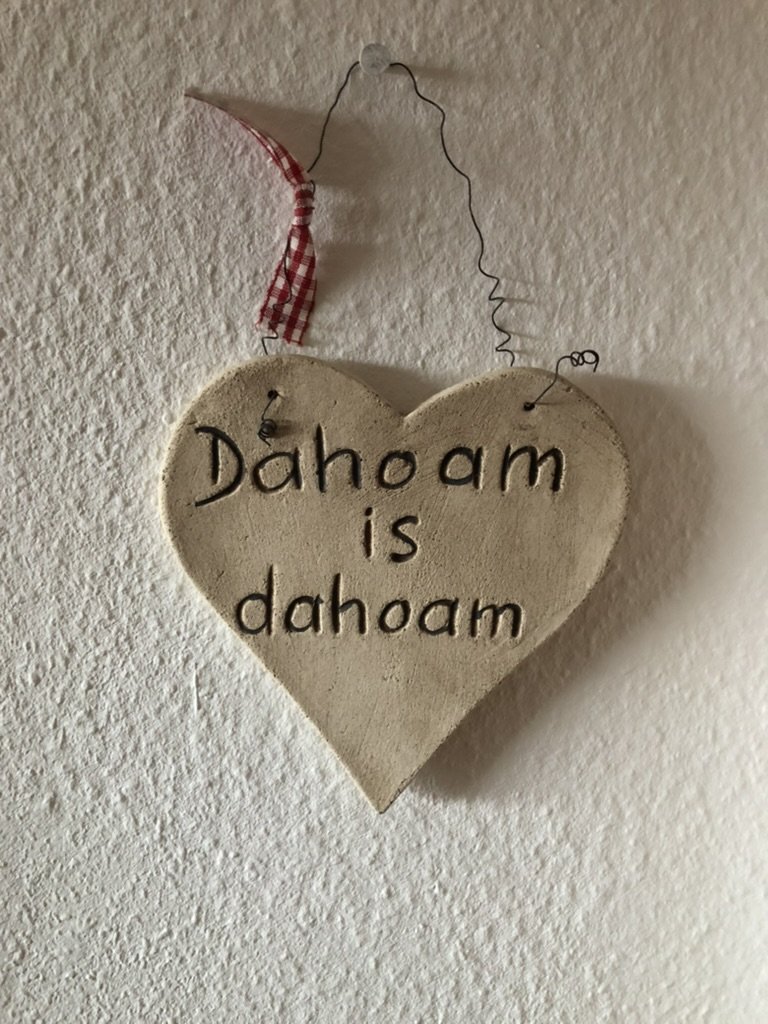

Sometimes I wonder if German isn’t so much a language as it is an umbrella term for the thousand variations on a theme. When I speak to my Bavarian neighbours, what I hear is not the standard German or Hochdeutsch I was taught in so many hours of classes at the Volkshochschule. Most are self aware enough to realise when they’ve strayed too far into dialect, or they simply look at my confused countenance and adjust when necessary. Others, such as the Kartoffel Bauer who comes to sell potatoes at the end of the street every Tuesday evening, can’t. He only speaks dialect, Schwabisch to be precise, and if you don’t know what he’s saying, well, no potatoes for you I’m afraid.

When you read about the history of the German language, you quickly realise that much of it is a story of the search for a standardised way of communicating across the country. From mediaeval merchants trying to sell their wares, or Protestant reformer Martin Luther printing the first German language bible, to the Brothers Grimm compiling the shared fairytales from across the country, all have had a hand in creating a version of German that can be understood by everyone, even someone as remedial as me. The reason for this quest for standardisation was that for centuries Germany was not only divided politically, but also linguistically. There wasn’t just one German language, there were hundreds.

The process of change wasn’t easy, nor was it always welcome. Many Germans then, as today, were proud of their versions of German that identified them as coming from a particular area or group, and they didn’t welcome the change. Writing was codified, but often the spoken language remained in defiance. Of course, progress was rather more of a steamroller than a welcome mat, and soon even the holdouts had to learn to communicate, especially once Germany became a nation in 1871. Many dialect speakers would learn standard German as a foreign language, much as I did, but they would still retain their own particular dialect in spoken form, passing it down to the next generation.

My own experience of living in different parts of Bavaria has been a lesson in how stubbornly many have protected their own dialects. In Nürnberg, I was exposed to Fränkisch, which to my untrained ears sounded like whole sentences made up of only B, D and double G sounds. I then moved to Augsburg, where Swabisch is the dialect of choice and everything seems to have this sweeping ‘Schhhh’ sound or is legally required to end in the diminutive suffix ‘-le’; sometimes because the thing in question is small, sometimes because it is cute, and other times because it’s just fun to say words that end in ‘-le’.

With all this dialect flying around, it might be assumed that the many versions of German were in rude health, however on closer inspection, that isn’t the case. As the late Germanic linguist Ulrich Ammon pointed out in the 1970s, dialect suffered from post-war conceptions of the correct way to speak German. Dialect was not only frowned upon wherever it was found, but it became interlinked with perceptions of intelligence. Hochdeutsch or High German, was the goal, not dialect. No one wanted to employ some dialect-speaking bumpkin, the orthodoxy ran, and so children across the country were taught standardised German, and still are today.

Books, most German TV and radio, and dubbed British or American TV shows all follow the standard version of German too, which has become a concern for those lovers of dialects. They see the creeping homogenisation of the language, and in somewhere like Bavaria, which prides itself on being different from the other 15 states, this is a real problem. It’s just another erosion of the native culture, another traditional value lost, so it comes as no surprise that there are those out there who fight to preserve it.

For an English speaker, especially from Britain, the discussion of dialect vs standard pronunciation seems familiar. For decades British children were taught that Received Pronunciation or the more grand “Queen’s English” was the goal of all speakers. This rather haughty, clipped version of English is still considered the standard in German schools, even though more modern preferences have taken hold in the UK. Where once the BBC was the beacon of standard pronunciation, through my lifetime I’ve seen different dialects of English become more prevalent and accepted. Now BBC newsreaders or announcers can come from around the country, and a Scouser, Brummy or Geordie isn’t automatically disqualified because they don’t sound as regal as they should. In Germany however, it might be a very long time before we hear dialect on the evening Tagesschau.

We may never see the varying dialect of German on the national news, but that doesn’t mean people aren’t interested in them. From my own experience I know that many local and national newspapers have monthly columns from linguists that promote dialects, while sharing the familiar and unfamiliar bits of dialect on Instagram can be a recipe for social media stardom. Others have been more focused on reopening education to dialect. In 2019, Bavaria’s Ministry for Education backed a project entitled "MundART WERTvoll” which seeks to promote and reward schools, educators, and pupils for projects that focused on Bavarian dialects. This is not to say that dialect was suddenly spilling into standard classes, but that schools were now looking seriously at how to bring students both standard and dialect German.

Of course, this wasn’t without criticism. The Bavarian Language Association has been critical of the fact that many would still hide their dialects in situations where they wanted to be taken seriously, and by doing so they were only furthering the deterioration of Bavarian variations of German. Others went even further: Ludwig Zehetner, a writer famous for his articles about Bavarian dialects, declared that the efforts to preserve Bavarian dialects was commendable, but decades too late. The damage had already been done, all these projects were doing was caring “for a corpse”.

Clearly at my level of German I’m no judge of the health of Bavarian dialects, but all I know is that I hear dialects far more than I hear standard German. If Bavaria’s dialects are dead, they’ve got a very funny way of showing it. Perhaps Germany has lost something from the drive for standardisation of language, but it doesn’t mean the end of dialects. I believe something so integral to people’s identities is harder to eradicate than that. Maybe some words fall out of favour, while others remain, but ultimately that’s how language works.

Proofreader: @ScandiTina

Image Credit

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Photo by form PxHere

Photo by form PxHere