A Pessimistic Optimist

Things feel gloomier than usual in Germany at the moment, which is really saying something, given the propensity for pessimism that bubbles under the surface here. I’m no stranger to the odd bout of national self pity, after all, the British have their own particular brand of melancholy. However, unlike the cheery British acceptance that things will usually be slightly shittier than we expect, German angst has a tendency to hang thick in the air, like an ever-present dark cloud. Though pessimism is a natural condition of life in Germany, there is at least a reason for the current sobriety, namely the recent EU elections that saw the far-right leap 11 points up on their 2019 result, and in so doing, becoming the second largest contingent of German politicians being sent to Brussels.

This feeling of dejection, expressed in many corners of the country, is further accentuated by the fact this should actually be a joyous moment for Germany, after all, they’re hosting their first major football tournament since 2006. The memory of that golden summer almost two decades ago still resonates, the Sommermärchen (summer fairytale) that saw a newly confident Germany reintroduce itself to the world. Despite losing to Italy in the semi-finals, people who experienced this moment describe it as not only a wonderful event, but as something that truly changed the nation. Sure, the pessimism remained, but there was a feeling that Germany had drawn a line under the past, allowing itself to begin a new, and possibly more, positive chapter in its history. That feels rather naive knowing what we now know, but that’s the nature of hindsight; what it offers in perspective, it loses in emotion, especially if the view is in or around any of the 16 Bundesländer.

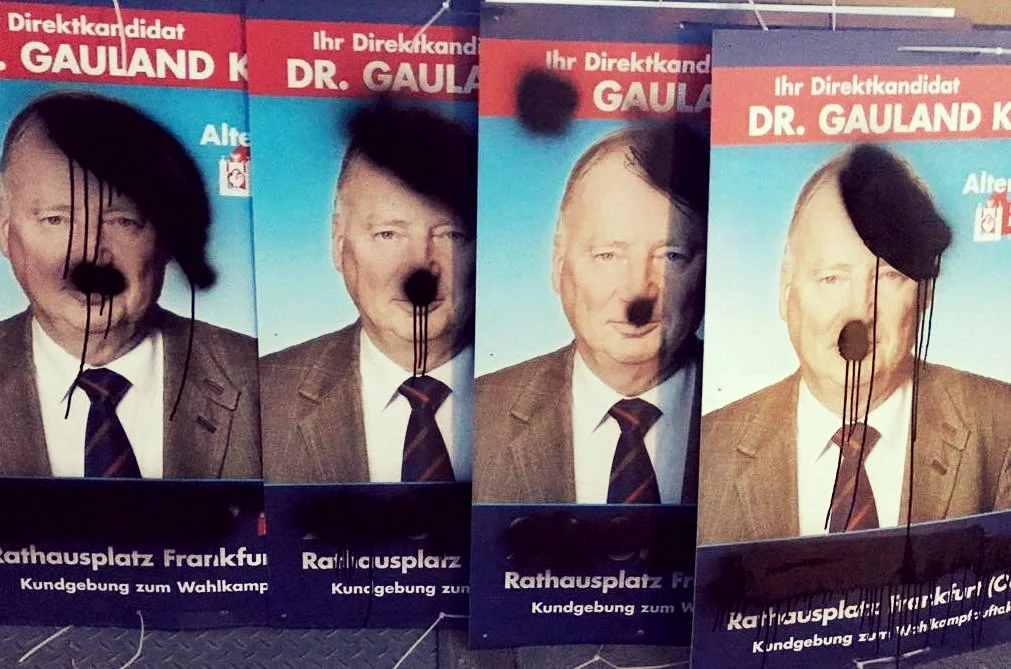

The shadow cast by the AfD’s record 15.9% last Sunday is long, and for good reason. There’s the historical aspect of course, but in modern minds it’s not only history that should be considered. The success of far-right parties, as bad as it is, should be considered a symptom of a larger problem, rather than the ultimate cause. Since the beginning of the pandemic, there has been a sense that Germany is in flux, the sands of certainty are shifting, shaking some of the most fundamental assumptions people have of their country. After the lockdowns, we entered a new world, one where trust was in short supply, and turmoil seemed to linger around every corner. Inflation, climate-change, house prices, wages, war in Ukraine - since 2021 it has felt as if we’re only minutes away from the next disaster, which is enough to make pessimism less of a national pastime as it is an objectively sensible understanding of the world around us. Yet, even for the most pessimistic German, the results of the EU election were surprising. Though perhaps not entirely a disaster, the fact that 16% of German voters under 24 cast their lot with the AfD was just another dark foreboding cloud added to an already overcast sky.

The reasons for Germany’s current solemnity are manifold, but what I find oddly galling is the surprise with which the AfD’s success has been met with among the media and the population at large. For over a year, we’ve seen support for the far-right grow, with accompanying headlines on an almost daily basis, analysing, warning, and generally hand-wringing. The polls suggested the outcome months in advance, yet when what is predicted plays out, the nation seems to react like a Southern belle, all theatrical emotion and light-headed astonishment. Perhaps I’ve acquired a more extreme form of German pessimism, bordering on plain cynicism, but the success of the AfD doesn’t surprise me, nor should it surprise anyone, since the reasons are plain to see, and have been, for a very long time.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m equally despondent as any other German about the results of the EU elections, and the regular polling that shows a significant growth in support for the AfD, but that isn’t the same as being shocked by it. Perhaps this is an indicator I’m not really as German as I thought; it may well be the case that shock is the natural reaction for Germans to the waves buffeting the good ship Deutschland. However, it does feel like the worst possible way to react, since shock can easily lead to despondency, and from there apathy is only a few footsteps away. This all the more concerning since no one seems to have an answer to the far-right’s recent success. Politicians seem ineffective, the best that many can think of is to create TikTok accounts, as Chancellor Olaf Scholz did only a few months ago. The reason for such a strategy is the recognition that the AfD have quietly grown their own social media machine, becoming one of the most successful operators in the places that young voters tend to spend their time. To win young voters back, so the logic goes, the other political parties must also enter the same arena.

There is a method to this approach, but the problems facing Germany won’t all be fixed by the nation's political class becoming part-time content creators. Like many people, I enjoy the odd TikTok trend, but no matter how many choreographed dance routines the Minister of Finance makes, it isn’t going to have much impact on the economy, nor will it build more houses. What politicians seem unable to do now, or seemingly at all over the last twenty years, is address the real pain points people have, their fears about their future, and futures of generations to come. For fifteen years we had coalitions dominated by Angela Merkel’s CDU, which provided stability, and therefore electoral success, but not a long-term fix to what ails the country. Moreover, that stability was clearly built on a foundation of sand, hope, and delusion, given the implosion of that much lauded aspect once Merkel left office in 2021. So complete was the collapse, it has tainted not only Merkel’s legacy, but smashed any hopes of the current government for their own agenda. Shortsighted decisions were the bedrock of Merkel’s time in office, from complete nuclear shutdowns to the idiotic decision to enshrine austerity into the fabric of the country’s constitution. While Merkel’s retirement has been a series of interviews with friendly back slapping journalists, the current coalition government has been left to pick up the pieces.

After all that, we can probably forgive the average German’s bout of existential angst, but are things really as gloomy as they seem? Well “yes”, but also resoundingly, “no!”. Germany can be pulled from the tailspin it's in, but it might take something that’s not naturally in abundance here: optimism. Not to plant too rosy a garden, but there are some things that seem to have been missed by the commentary since last Sunday. First and foremost, this was an EU election, which doesn’t necessarily equate to a national election. People might be comfortable sending AfD politicians to the EU parliament, but it doesn’t mean they want them governing their cities or their states. As if to underline this fact, in the AfD stronghold of Thuringia, which had local elections at the same time as the EU elections, the AfD grew their vote share, but failed to gain control from districts it was assumed they would win. Nine candidates in Thuringia now face tough runoff elections, with no guarantees of victory.

This may seem like a rather dim bright spot, but there is one other factor that Germany seems to be missing: there’s a very good chance that as the AfD grows, they will become their own worst enemy. The AfD has been prone to splits before: in 2017, the day after a successful Federal election for the party, one of their leadership quit the party in a very public fashion. This division has continued, seeing splits appear in other areas. Again, during local elections in Saalfeld-Rudolstadt, the AfD had two separate lists of candidates, reflecting the power struggle between state AfD leaders. On top of that, the brains behind the much lauded social media strategy of the AfD, one Erik Ahrens, reacted angrily to the treatment of his preferred candidate and publicly attacked the national party on social media. Though it will take more than waiting for the right-wing to implode, a party filled with so many extremist egos will be hard to manage going forward.

Ultimately, the gloom may lift for a few weeks, should the German national team buck their trend of big tournament failure from the last few years. It will be welcome respite for everyone, though the pessimism will more than likely continue. I’ll try to remain optimistic, it’s at least better for my mental health than the alternative. Still, no matter what the outcome, I’m still cheerily convinced it will be ever so slightly shitter than I expect.

Proofreader: @ScandiTina

Image Credit

Photo by David Babayan on Unsplash

Photo by Eyestetix Studio on Unsplash

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

Photo by Levi Meir Clancy on Unsplash

Photo by Aumi on Unsplash

Photo by Jakob Owens on Unsplash