Crucifixes and Pretzels: The Symbols of Bavaria

Increasingly, life in 2018 has come to resemble a terrible tribute act to a band that no one really cared for, performing half remembered songs, for an audience of deaf people. Truly we live in the strangest of times. Far-right politics have returned, a second Cold War looms, there is another celebrity occupant of the White House and here in Bavaria we are once again working through the myriad of debates concerning the place of religion in politics. Surely our ancestors could be forgiven for thinking that by 2018 we may have progressed a little further, and I suppose we have; I can now watch all this occur in 4k High Definition, while hurling obscenities at minor celebrities on Twitter. Ah, progress.

Bavaria’s current religious debate centres on its State President, Markus Söder (CSU) and his decision to require crucifixes to be hung on the walls of all state government buildings. This has caused consternation for the scholars of Germany’s constitutional Basic Law, due to its clear violation of rules governing religious neutrality. When this was put to Mr. Söder, he claimed that there was no violation, given that the crucifix was part of “Bavarian identity” and doubled down with a logical leap of faith, declaring that the crucifix itself “is not a sign of a religion”.

Criticism of Mr. Söder was swift and unflinching. Cardinals, journalists and young Christian groups all came out in opposition to what they perceived to be the use of religious symbols for political gain. With state elections coming in Autumn, Söder’s Christlich-Soziale Union (CSU) is on the defensive against a feared increase in the vote for Alternative für Deauschland (AfD) who inhabit the right-wing of the German political spectrum. It is clear that Mr. Söder hopes to galvanise his supporters behind an image of the Christian Social Union, and himself as protectors of traditional Bavarian norms. Political rivals also joined the fray, with Christian Lindner, leader of the Die Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP), taking to Twitter to compare the Minister President to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the authoritarian President of Turkey. Linder, of course, should know something about mixing religion and politics, given the cult of personality he fostered during the recent general election last Autumn.

In fairness to Söder, he does have a point; Bavaria is an overtly religious state. Take a drive through the Bavarian countryside and it won’t take long before you pass a house with a large mural dedicated to St Christopher or find a small shrine to the Virgin Mary, surrounded with fresh flowers. Religious festivals are still the framework for most public holidays, with nine days given over to everything from Christmas to All Saints Day. Climb a mountain or even a small hill and you will likely find a cross at the top or buy a beer and find it was brewed in a local monastery. Christianity is hard to miss here in Bavaria and it is unsurprising that Mr. Söder wants to bring back Christian symbols, when the word Christian itself is one third of the name of his and Bavaria’s governing political party (Christian Social Union).

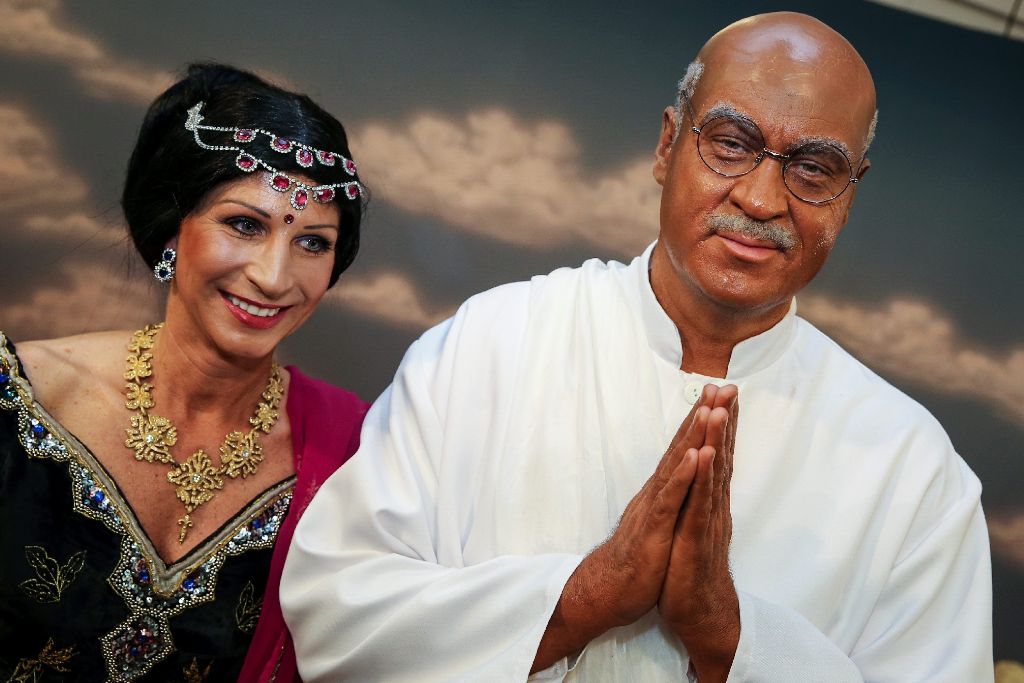

It is also unsurprising that Mr. Söder would aim to weaponise the Bavarian religious right with publicity stunts, rather than useful policy. Why go to the bother of creating policies to benefit everyone, which would take time and effort, when you can buy a job lot of crucifixes on ebay and create a shitstorm of publicity? Politics is time consuming work and as Bavarians will know, Mr. Söder has so little time, given that he must spend months trying to decide what zany costume he will wear during Fasching celebrations. In the last few years he has gone in drag, as a punk or that time in 2015 when he blacked up and went as Ghandi. Mr. Söder knows what the people want, crucifixes in the tax office and racially insensitive costumes.

Then again, how Christian is Bavaria really? Sure, census data suggests that 9 million Bavarians out of a total 12 million identify as Christian. However, when we look at regular church attendance we find that only 3.5% of German protestants and 10.2% of German Catholics go to church with any regularity. Perhaps Mr. Söder could reflect on these stats and only put a crucifix on the walls of 13.5% of government buildings. Alternatively, he could only put up a crucifix at Christmas and Easter, which would reflect the regularity of attendance at most church services.

In the end, perhaps putting up a crucifix was the least contentious thing Mr. Söder could have done. Imagine if he had suggested putting up a Breze (Pretzel) and declared it a symbol of great import. The whole state would go up in flames as Breze zealots from the Oberpfalz to Munich declared that everyone else’s brezen were heretical and the one true Breze was actually baked in their home village. Worst still, he could have pinned an Erdinger label to the wall and watched as the whole of Frankonia rose up in violent revolt. There is an old adage that suggests that beer, religion and politics don’t mix, maybe Mr. Söder could add Breze to the list and forget this tacky attempt at popularism.