Why People Vote for the AfD

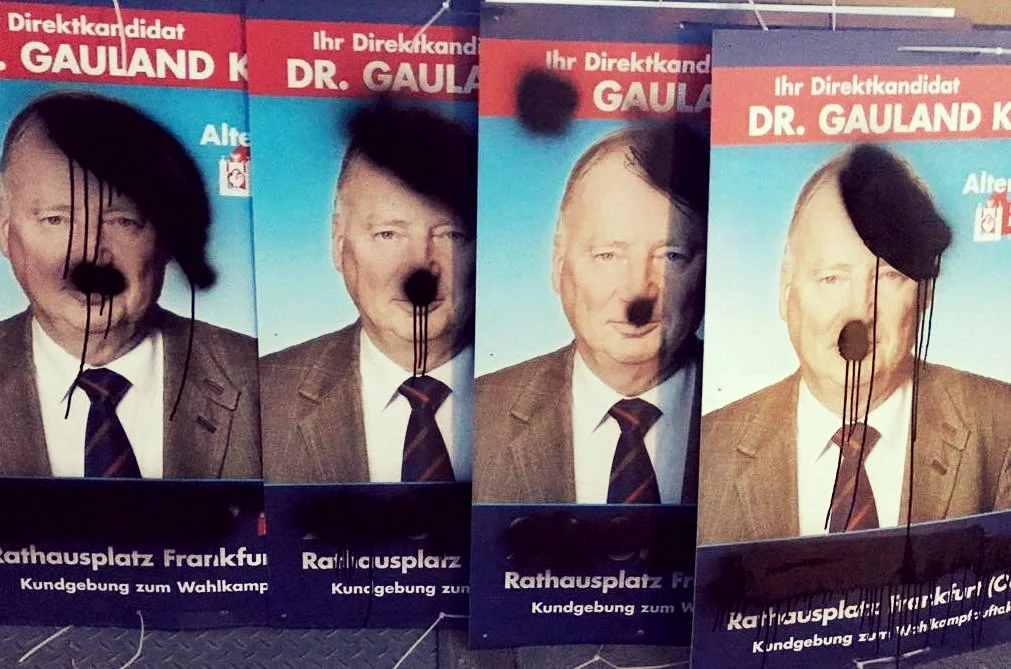

Cover image: no-afd.tumblr.com

Germany’s election season is nearing an end, the culmination being this Sunday when the German electorate finally reaches the polls. With Angela Merkel and the CDU’s (Christlich Demokratische Union) victory all but confirmed, much of the reporting here in Germany and around the world has been focused on the emergence of the AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) as potentially the third largest party in Germany. This has obviously led to some soul searching within the German media, concerned with what the right-wing parties' arrival in the Bundestag means. The historical overtones are hard to ignore, given that the election of AfD candidates to the national assembly will mark the first time a far right party has entered the legislative body since 1933.

Electoral success is not the only comparison being made between the AfD and the National Socialists. The AfD’s cultivation of far right supporters, the use of Nazi era rhetoric to stoke anti immigrant fears and their protestations over how German history should be remembered all contribute to a feeling that the AfD are a revival of a political movement that many had hoped to have died in 1945. I have seen no clearer example of this position than the numerous defaced AfD placards and billboards around Nürnberg, daubed with the words “Nazis Raus” (Nazis Out) in black spray paint.

Image: no-afd.tumblr.com

Although the results of the election are yet to be confirmed, the AfD are not expected to win seats outside of the Eastern states of Germany. Even so this election, the second I have seen while living in Germany, has been marked by the growth in AfD political advertising here in Bavaria. Germany’s southern most state has been dominated by the CSU (Christlich-Soziale Union), the sister party of Merkel’s CDU, for as long as many people can remember. The CSU has been part of an overwhelmingly successful political strategy for the leaders of Germany’s largest party, allowing a more conservative and right leaning position to be promoted, while the main party maintain a centrist position nationally. This alliance has not come without a cost and conflict has emerged in recent years, focusing heavily on Merkel’s decision to allow refugees to settle in Germany in large numbers.

Even though the AfD are unlikely to win over the Bavarian electorate, the strategic placement of their posters and billboards in low income areas of my adopted city reveals something of the strategy that they have used to emerge from relative political obscurity. It is common for critics and opponents of the AfD to label the party and its supporters as neo-Nazis and idiots and although I am sure their support has many in their ranks that could be described as such, I feel this representation belies the real reason the AfD have become potentially the third party in Germany.

The heartland of the AfD is the East of Germany and in states that are recognised as the poorest of the sixteen Bundesländer. Areas where the AfD has had electoral success in regional elections include Saxony, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Saxony-Anhalt. This is by no means a coincidence. Initially the AfD leadership of Bernd Lucke refused to work alongside UKIP because it was too nationalist, but in recent times (under new leadership) the AfD has shifted further and further to the right of the right-wing and picked up votes from those who still espouse the virtues of National Socialism. Yet, as they did so, they have also picked up votes from those on the lowest rung of the German economic ladder, those who have not seen a share of the wealth that made Germany impervious to the economic crises that so rocked the EU.

These voters have come to see a vote for the AfD as a vote against the status quo. This goes some way to explaining why voters in Berlin, traditionally seen as the most liberal of Europe’s capital cities, gave them 14.5% of the vote and 25 seats in the state parliament. Additionally, in Baden-Württemberg one of Germany’s richest states they gained 15.1% of the vote and 23 seats. Not everyone is satisfied with the boring and stable landscape of German politics, the economy maybe stable but as statistics show, the wealth gap has grown. As a recent study by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) points out, unemployment maybe down but that has not led to prosperity for all. The risk of low income earners falling into poverty is highest in the East of Germany, but it is a problem for everyone who happens to occupy that bracket. When 60% of German wealth is possessed by only 10% of the population, the most vulnerable in society can hardly be expected to see the economic success of Germany as a benefit to them.

The political parallels with the UK are acute, where policies of austerity and financial purges on the benefits of the lowest earners directly led to the shocking Brexit vote in 2016. The poorest in society had been force fed tales of sacrificial belt tightening due to a fabricated fear of public debt, they were told that “We are all in this together” and then watched as the rich got rich and the poor got poorer. They became targets of UKIP and through fear of the right vote splitting, David Cameron and his Tory chums acquiesced to a needless referendum, safe in the knowledge that they would win. Over confidence in ones ability to steady the ship can lead to it sinking without trace.

Germany can ill afford to ignore the impoverishment of the population at large. For all the tales of investment in East German infrastructure, skilled work and opportunities for young people are thin on the ground. I am frequently told by friends that the Eastern states have some of the best roads in Germany, paid for via a solidarity tax on the rest of Germany. Well built roads are all well and good, but they are useless if no one can not afford a car to drive on them. Germany may have a much celebrated export market, but this only throws in contrast the fact that child poverty is growing year on year. That children, supposedly the one resource Germany most needs to avoid demographic catastrophe, are increasingly falling into poverty is the hidden shame of German politics and Angela Merkel’s government.

Image: dw.com

The next four years may be the toughest of Merkel’s much vaunted career, and if she continues to ignore the problem or worse throw crumbs of comfort into the maw of decreasing infrastructure spending, she will only have her self to blame as the AfD grows larger, feeding on the inequality that she has presided over. The Twitterverse, commentators and others may scream Nazi at the AfD and rightly so, but if Germany continues to watch jobs be “Off Shored” and allow wholesale automation to eviscerate skilled jobs, before long we may all be wondering why everyone is voting for the despicable AfD.